[[[[This article is good for nothing.]]]]

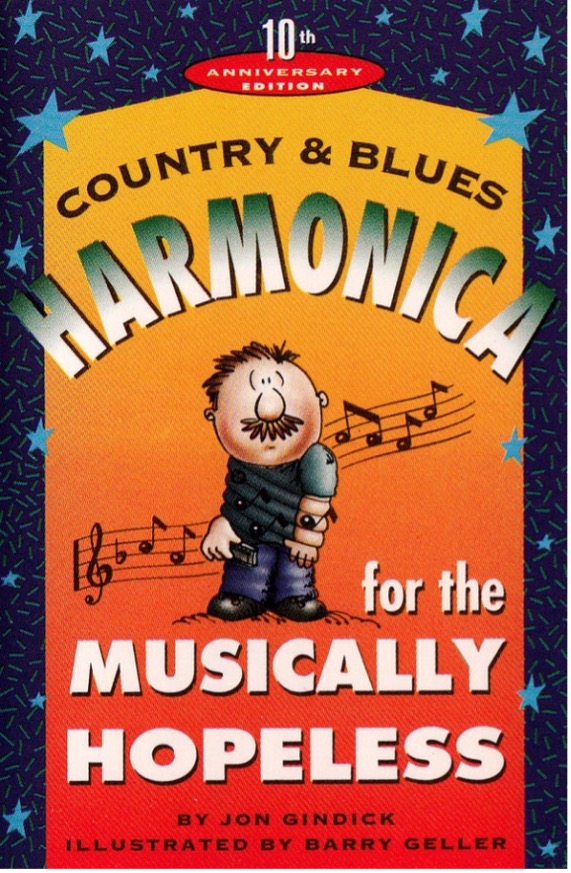

As I allude to in most of my writing, the past decade has been one of immense change in how I understand my role as an artist and, more generally, my place in the world. My pathway into music unfolded rather more through chance than design. Records would often be playing at home and my father was wont to summon a tune every now and then on the harmonica, the guitar, or in his rich baritone voice. My career as an instrumentalist began with a toy drum-kit, soon graduating to a blues harp purchased on a family trip to Canada and the US around 1994 (a Hohner Pocket Pal, which I still have[1], together with a tape and a book, more on which later). In 1997, the fateful letter came home with me from junior school: does your child want free violin lessons? (Yes, that’s right kids, instrumental lessons were free!). There began, initially to my parents’ great dismay (violin beginners make for terrible neighbours), nearly three decades of intense study (so far), a journey of bizarre contradictions, intense highs and lows, fascination, anxiety, and occasional ecstasy, but those are tales for another day.

Suffice it to say that the last third or so of my time with the violin, coinciding with a deepening investment in politics and spirituality, has seen many things flipped on their head. Where before music was just music—heart-pumping, mind-bending, spine-tingling music, but just music nonetheless—now I understand it as part and parcel of the everyday, utterly of its time, affected by and effecting everything around us, from the minute to the monolithic, heavy with meaning and enormously powerful. As a wise man once cautioned Peter Parker, ‘with great power comes great responsibility’ (Cronin, 2015). British free improviser Eddie Prévost points towards the necessity of developing just such a sense of responsibility in musical sites (Prévost, 1995). The changes in my artistic and personal life (often one and the same) over this period have been largely dictated by an ongoing rumination on how this responsibility can best be exercised in my practice. Author Matt Cardin recently published an article entitled ‘Art as Trap and Transcendence,’ posing a unique challenge to art: ‘[d]o art and life stand in conflict? Does each injure the other, steal from the other, sap the essence of the other?’ (Cardin, 2024). In all my years wrapped up in music, I can’t recall ever having pondered such a fundamental question. Cardin doesn’t come to a conclusion as such, instead recognising that art can be both trap and transcendence, but more importantly situating the dialectic within the context of nonduality, wherein neither position can be true. In absolute terms, the separation of things is an illusion, one by which ‘we’ are constantly duped (and in Buddhist terms, a delusion which traps us in an endless cycle, ‘Samsara,’ of rebirth and suffering), and therefore ‘[t]he whole anguished conflict plays out for a shadow, a phantom, a dream self within the real Identity’ (Ibid.). Cardin’s writings are notable as they posit that much of our philosophising about art and life is constructed on non-existent ground. In the political sphere, it might be akin to the prevailing culture in mainstream journalism of spotlighting ‘froth stories,’ pulling attention away from entrenched, invisible institutions and systems of imperialism and domination, disguising the latter as unquestionable facts of nature (Novara Media, 2024, 26’05”).

In recent conversations, I’ve encountered a similar dichotomy in attitudes about musical practice. Some see it as escapism (trap), others as activism (transcendence). On a mundane level, I would offer a counter to the ‘trap’ pole on the basis that even art which seemingly takes us out of the everyday affects the individuals and communities touched thereby. There can be no separation between the world of the real and the world of the artwork, as the audience carries one into the other. We create and mediate the world of the real through our experiences, and our experiential lens is altered every time we interact with anything. Engagement with the arts therefore changes the creation and perception of the everyday. To assume a separation is to fall victim to the fundamental fallacy. Art is the everyday, the everyday is art.

Composer, trombonist, and author George Lewis of the AACM espouses this same conviction in the field of improvisation:

‘Working as an improviser in the field of improvised music emphasizes not only form and technique but individual life choices as well as cultural, ethnic, and personal location. In performances of improvised music, the possibility of internalizing alternative value systems is implicit from the start. The focus of musical discourse suddenly shifts from the individual, autonomous creator to the collective—the individual as a part of global humanity.’ (Lewis, 1996, p. 110)

If Lewis’ assessment is correct, this form of musicking cannot be understood as apart from life in general; the idea makes no sense. Through such an artistic practice, one’s connection to the world is deepened, community is strengthened, ethical values are evaluated and internalised (Small, 1998). This is not to suggest that the outcomes of such art-centred modes of inquiry will be unimpeachably positive, only that they are inherently grounded in social realities. Admittedly, music and literature function differently, temporally, spatially, and in terms of the requisite interactions and processes, but I see no reason why Lewis’ assertion ought not to be a potential situation across both media. This brings me back to the aforementioned harmonica instruction book, which a search engine quickly identifies, hitting me with a powerful wave of nostalgia, deliciously sprinkled with delightful irony. ‘Country & Blues Harmonica for the Musically Hopeless,’ published in 1984, is a step-by-step manual for playing the blues harp by ‘America’s best-selling harmonica instruction author’ Jon Gindick (Gindick, n.d.). My old copy (sadly lost at some point over the years) featured a blue and yellow cover, with a cartoon by Barry Geller of a cutesy moustachioed character (not too dissimilar to my very own harp playing pop) unfortunately enmeshed in some pesky musical notation. Gindick positions himself as the ‘Musical Last Chance’ of ‘[t]he tin-ear contingent, the piano lesson drop-outs, The Hopeless Ones’ (Gindick, Country & Blues Harmonica for the Musically Hopeless, 1984, p. 10) (Gindick, Country & Blues Harmonica for the Musically Hopeless, 1984, p. 10). This book represents my first formal didactic experience, so I suppose Gindick rightfully earned his dollars that day. I dutifully worked my way through the tunes on offer, etching ‘When the Saints Go Marching In,’ ‘Camptown Races,’ ‘She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain,’ and other classics into my mind and body[2].

What, I hear you ask, does this nostalgic navel-gazing have to do with traps and transcendence, nonduality, alternative value systems, or artistic responsibility? I’m going to approach Cardin‘s dichotomous conundrum at the heart of artistic practice from a somewhat alternative angle, taking hope and hopelessness as a starting point, rather than nonduality.

Buddhist teacher and author Ethan Nichtern identifies hope as one of the two poles of the ‘eight worldly winds,’ known as such ‘because whenever we become attached to some plateau of stillness or ease, these experiences can knock us off balance’ (Nichtern, 2024, introduction). Presented as four pairs, on the one side reside the things we tend to reach towards (the hope pole), and on the other the things we try to avoid (the fear pole). Nichtern labels the pairs as pleasure/pain, praise/criticism, fame/insignificance, and success/failure (Ibid.). What I find fascinating about this framework are not the aspects of fear, which are commonly accepted as undesirable experiences; rather, it is the notion that hope is no less responsible for our persistently unmindful and reactive states of being, and ought not, therefore, to be unreservedly labelled a beneficial quality. Hope is so faithfully valorised in our contemporary cultures that Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign hung almost entirely on fostering this sentiment in the popular imagination of the American public.

Perhaps Gindick, unwittingly or otherwise, struck upon something profound in his tongue-in-cheek branding.

The Zen monk Kodo Sawaki was fond of declaring zazen (Zen meditation) ‘good for nothing’ (Uchiyama & Okumura, 2014, p. 138). Kosho Uchiyama recalls how, when he asked his teacher Kodo whether he could become ‘even a little bit stronger’ through the practice of zazen, Kodo replied ‘[n]o, you can’t. No matter how hard and how long you practice, zazen is good for nothing’ (Ibid.). In typically paradoxical Zen fashion, however, Kodo seems to hint that good-for-nothing practice might actually be good for something:

‘…practice good-for-nothing zazen without any expectation. Otherwise, our practice really is good for nothing.’ (Ibid.)

Since reading these teachings, the idea of ‘good for nothing’ has occupied my mind. Kodo insists on the emptiness of the practice, and yet advises others to carry on nonetheless, himself practising zazen for many decades; a wholehearted commitment to a good-for-nothing practice.

What would this look like, I have found myself pondering, in a musical context? In what way is musicking good for nothing? Whenever we talk about music, we typically aim to extol its virtues. In Britain in 2024, for example, many of the arguments about music revolve around its place in schools. We should be getting music back into mainstream education because it’s good for confidence and team building, coordination, problem solving, numeracy, amassing cultural capital, listening, discipline, and so on, all of which is undoubtedly true. Our concept of ‘good,’ however, is heavily conditioned by capitalism. Perhaps being good for nothing means being good outside of the framework of a capitalist understanding of value and transaction.

Two of the questions which are commonly asked when I interact with audience members, particularly in unusual forums outside of the conventional performance spaces, are ‘do you do this for fun?’ and ‘are you a university student?’ Although likely well-meant, there often lurks the spectre of a veiled bafflement beneath the pleasantries, an inability to understand how such a way of being interfaces with, and is sanctioned by, a capitalist system, perhaps even a whiff of accusation: ‘they pay you to do this?’ [1] On the one hand, most people consider themselves fans of the arts in some sense (even if they wouldn’t articulate it as such), but on the other, those professionally involved in the arts might as well be from another universe. The arts are invaluable, unquantifiable, and therefore cannot exist within a transactional paradigm of engagement in anything other than a hobbyist, ‘extracurricular’ fashion (this is factually untrue, of course, as the arts do exist as commodities; the argument I am making here is that there is an intuitive tension inherent in the dialectic of art and money, which often seems to cause a meltdown in people’s heavily conditioned operating systems).

I wish to return now to my youthfully naive attitude of just music. I’d like, in fact, not to reject it, but, on the contrary, to commit to a practice of ‘hopeless just-ness,’ not in the sense of casual leisure-time fun, but rather in the Buddhist sense of shikan. Uchiyama elegantly summarises this concept:

‘[Thirteenth century Zen monk] Dogen Zenji often used this word as “just doing” or “doing single-mindedly.” This doesn’t mean experiencing ecstasy or becoming absorbed in some activity. To experience ecstasy or absorption, an object is needed. Shikan has no object. It’s just doing as the pure life force of the self.’ (Uchiyama & Okumura, 2014, p. 229)

This brings us conveniently back to Cardin’s ‘anguished conflict [playing] out for a shadow, a phantom, a dream self within the real Identity’ (Cardin, 2024). Playing music is playing music. I am not playing music. There is music, and later there isn’t. The liberatory potential of the arts is rooted in their ability to give the lie to supposedly fundamental truths about separation which can lead only to suffering. Joy is seeing the shadow, the phantom, the dream, and realising that there never was a dreamer.

Trevor Leggett, in his 1978 book ‘Zen and the ways’ (Leggett, 1998, pp. 230-231), tells a tale[2] of a student flautist who, despite obvious technical mastery, is invariably told by his master that the piece he is trying to learn has ‘something lacking’. After falling into despair and becoming a recluse, the student eventually receives a visit from his old master and his master’s youngest apprentice. They request that he perform at the annual assembly. Before the performance, the hopeless student realises that ‘now he [has] nothing to gain and nothing to lose.’ Emancipated from any attachment to illusory notions of good and bad, self and other, failure and success, out of reach of the worldly winds, the flautist plays ‘like a God!’

Through hopeless just-ness, let us be good for no-thing.[3]

John Garner

[1] This harp appears on the album ‘Movie Night,’ available on Difficult Art & Music.

[2] Everyday I’m increasingly aware that, like most people, I have a peculiarly hodgepodge bank of internalised melodies which occasionally float of their own accord towards the surface of consciousness. This book represents one such source for me, as do several years as a teenager spent with the West Midlands Light Orchestra (fortuitous preparation for an unexpected career in jazz music).

[3] Sometimes people say the quiet part out loud: years ago whilst busking at Covent Garden, an elegant older woman approached my colleague to politely inform him that his mother must be dreadfully ashamed of him. To his credit, he burst out laughing.

[4] I first encountered this story via Stephen Nachmanovitch’s retelling in his 1990 book ‘Free Play’.

[5] I am grateful to Matt Cardin and Will Edmondes for their generous feedback on early versions of this article.

Works Cited

Cardin, M. (2024, June 28). Art as Trap and Transcendence. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from The Living Dark: https://www.livingdark.net/p/art-as-trap-and-transcendence

Cronin, B. (2015, July 15). When We First Met – When Did Uncle Ben First Say “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility?”. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from CBR: https://www.cbr.com/when-we-first-met-when-did-uncle-ben-first-say-with-great-power-comes-great-responsibility/

Gindick, J. (1984). Country & Blues Harmonica for the Musically Hopeless. Palo Alto: Klutz Press.

Gindick, J. (n.d.). Jon Gindick: Harp Teacher. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from Country & Blues Harmonica for the Musically Hopeless (Hopeful): https://gindick.com/product/country-blues-harmonica-for-the-musically-hopeless-hopeful/

Leggett, T. (1998). Zen and the ways. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

Lewis, G. E. (1996). Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives. Black Music Research Journal, 22, 91-122.

Nichtern, E. (2024). Confidence: Holding Your Seat through Life’s Eight Worldly Winds. California: New World Library.

Novara Media. (2024, June 30). On Intelligence Services, Corporate Media & Propaganda | Ash Sarkar meets Matt Kennard. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ig-ARHqXVxw

Prévost, E. (1995). No Sound Is Innocent. Harlow: Copula.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

Uchiyama, K., & Okumura, S. (2014). The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.