Whilst contemplating what to write about for this article, a Tarot draw revealed three Knights in a row. Characters of action, intention, energy—a clear indication to move—but towards what were these intense figures pointing? A fourth card for context produced the Three of Wands.

I couldn’t help feeling excited about the appearance of the number three, as though the wands emerging from the earth, connected via an umbilical cord to a patient, inquisitive mother, represented three aspects of a practice, three pillars of creative being, embodied in the Knights. Patrick Valenza, the artist behind the Deviant Moon tarot deck, beautifully describes the Three of Wands as ‘represent[ing] the circulation of creativity from one form to another’ (Valenza, 2016, p. 211).

Reflecting on the ‘circulation of creativity’ in my own artistic journey thus far, in this article I consider certain areas of practice in response to the three Knights, drawing on my experience as both a student and a teacher (often one and the same), shifting between the practical, the psychological, and the spiritual.

Straight out of the gate bounds the Knight of Wands. A salient beginning, as Wands is the suit of fire: action, intention, eagerness, movement (Pollack, 1997, pp. 161-162). Kate Van Horn identifies this card as one of ‘bold vision’ (Horn, 2024, p. 202). In the same way that Triratna Buddhist Community founder Sangharakshita points towards meditation as a way, not of conjuring some particular state, but rather of removing hindrances to entering higher states (Sangharakshita, 2010, p. 163), cultivating a sense of where we are heading can help awaken powers of intuition which seem to draw one inexorably along a path of meaningful growth and transformation. It’s important to add, however, that I’m not advocating for an achievement-oriented mentality. Achievement is often predicated upon ideas about oneself as seen through the eyes of others, even if that other is an imagined version of oneself, and is therefore centred around an attitude of self-improvement, only possible through a commodification of the self.

Instead, the vision to which I’m referring is rooted in the authentic self, a vision tempered by patience and faith. Writing about the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism, Thich Nhat Hanh tells us that ‘[t]he Buddha said that Right View is to have faith and confidence that there are people who have been able to transform their suffering’ (Hanh, 2008, section on ‘Right View’). This might seem to take us some way outside of the purview of artistic practice. If, however, we are committed to the transformatory and liberatory potential of the arts, then the words of the Buddha are not at all irrelevant. A creative life lived with ‘Right View’ is one embedded within the lives of others; one that recognises the extraordinary change that has been effected by artistic forebears; and one that strives for something better, for emancipation from suffering for all sentient beings. We live in a fraught time; in the quest for universal healing, adrienne maree brown situates vision as primary: ‘first we imagine’ (brown, 2017, ‘The Beginning of My Obssession’ section).

I spent many years as a music student without a clear idea of where I was going; or, to put it more honestly, with many ideas borrowed from others. From a young age, it was assumed, by me and those closest to me, that I would become a professional musician. Much of what followed happened almost automatically, as though the path was already paved. This isn’t to say that there wasn’t blood, sweat, and tears; only that the direction of travel, and therefore the appropriate places to focus energies, was straightforward.

A personal ultimatum of sorts, brought on by worsening anxiety and chronic playing-related pain, initiated a process of intense reflection which continues to this day. Although I intend to write about these experiences in detail at some stage, suffice it to say here that this process has radically transformed my artistic, professional, and personal life, in some ways knitting the triptych together in a way that had previously been lacking. Where before much of my vision as a musician was turned inwards, trapped and darkening, disconnected, unplugged, now I seek to open my practice to the world around me, in turn allowing the energies and necessities, the joy and the suffering, of the outside to inform all aspects of my creative growth and pursuits. In this way, to borrow poet and playwright David Budhill’s apt description of improviser William Parker, I feel myself moving closer to being ‘at once both fully inside [myself] and fully outside [myself] and therefore attentive to the world’ (Parker & Budhill, 2007, p. 16).

This has perhaps most obviously manifested in my near total shift away from Western classical music[1]. Until around 2009, my formal musical education (supplemented, of course, by varying informal pursuits) had been entirely rooted in Western classical studies. This is a good example of the paved path of unquestioned travel: I decided, spur of the moment, to take (free) violin lessons at school with a classically trained teacher; I took to it easily, and there were opportunities aplenty in that time and place for an aspiring young musician. Fast forward a decade or so and I found myself at the Royal College of Music, where the tension between expectation and inclination became impossible to ignore, leading to the aforementioned ultimatum.

A chance opportunity to take jazz violin lessons as a second study led ultimately to a career rooted in jazz and improvised music, embedded in a mutually supportive community that challenges me to answer the demands of the moment through my voice and platform. This has been a process of (re)integration, echoing AACM musician, composer, and author George Lewis’s words: ‘the development of the improviser in improvised music is regarded as encompassing not only the formation of individual musical personality but the harmonization of one’s musical personality with social environments, both actual and possible’ (Lewis, 1996, pp. 110-111). Western classical music was not a forum within which I felt able to harmonise with the ‘social environments’ that felt true and important to me. I seek here not to make any criticism of the structures or workings of Western classical music (though there is no shortage of literature on the topic: for a good primer, see Christopher Small’s ‘Musicking’), but simply to reflect on how an inability to be honest with myself about my conflicted relationship with the tradition was a destructive one that both warped my sense of self and prevented me from developing a moral practice that could do ‘meaningful work in the world’ (Fischlin, Heble, & Lipsitz, 2013, p. xv).

Privileged now to work as a teacher with students of all ages and abilities, I endeavour to encourage them to reflect on their music making as a fertile site of interconnection and interrogation, situating their artistic practice within the bedrock of their daily lives, ‘emphasiz[ing] not only form and technique but individual life choices as well as cultural, ethnic, and personal location’ (Lewis, 1996, p. 110). I am extraordinarily grateful to all the teachers who have given so generously to me of their time and wisdom. I hope to honour that gift by passing that wisdom on in such a way as to avoid any of my students having to discover the hard way that ploughing ahead with eyes closed is a recipe for disaster. What’s more, with open eyes you are ‘liberat[e]d to realise your true status as a single node in a cooperative network’ (Yunkaporta, 2019, ‘Lines in the Sand’ section), able to ‘know [yourself] as individual and universal at the same time’ (Blackstone, 2023, p. 27). For Sōtō Buddhist priest Uchiyama, in seeking ‘the truth of our selves and creat[ing] our own spiritual life… we give birth to the potential that can point the way for our time’ (Uchiyama & Okumura, 2014, p. 20), thereby allowing us to answer the challenges of the moment with authenticity and groundedness.

The Knight of Cups appears second, the suit of water, a much-needed counterbalance to the dangerous hunger of fire: ‘if not controlled and directed, that energy burns up the world… without water the summer sun brings only a drought’ (Pollack, 1997, p. 162). Here is an invitation to temper the heat of inspiration and the flames of passion with the humble yet awesome waters of the emotions: ‘[t]he suit of Cups shows an inner experience that flows rather than defines, that opens rather than restricts’ (Ibid., p. 185). Channelling the spirit of her father Bruce Lee’s philosophy, Shannon Lee reminds us that water ‘will carve canyons into mountains’ (Lee, 2020, p. 18).

Water is a theme that makes frequent appearances in my creative and pedagogical life. Flow is everything. Movement is the true constant. In the words of visionary author Octavia Butler, ‘God is Change’ (Butler, 2014, chapter 1). I’ve referred to the playing of guitarist Allan Holdsworth, one of my heroes, as ‘elemental… fluid… Holdsworth could conjure the stillness of a softly-rippling mountain lake [or] the fury of an ocean deity riding the primal storm’ (Garner, 2022). Double bassist John Pope and I titled our first album of compositions by late twentieth-century jazz trailblazers ‘Water Music,’ after a melody of the same name by Mary Parks and Albert Ayler, featured on the 1971 LP ‘The Last Album.’

Over the past months, I have been immersed in a research project in which I record and release an album of improvised music for solo violin once a week. As of the time of writing, the Glues Browling series runs to 46 volumes. Forty minutes a week may not sound like a big ask, but when you set about doing this week in, week out, recording and releasing the results, it’s not all plain sailing. Inspiration, at least in my experience, is not limitless, nor is improvisation unaffected by the ebb and flow of daily life and all the emotions that arise (I’m trying to resist the pull of water metaphors, only to realise how baked into language are experiences and ideas rooted in the fluid). This has necessitated a certain attitude of acceptance, a willingness to—if you’ll forgive me the much-abused phrase—go with the flow. Zen rōshi Maurine Stuart draws this same connection between immersion and flow: ‘[i]f we are so much with what we are doing that there is no room for anything, then we are in direct contact with the flow of our lives, with the flow of Buddha-nature in us, working through us’ (Chayat, 1996, p. 34). The Glues Browling series has been a meditation of sorts, what Japanese philosopher Yasuo Yuasa might term a meditation through ‘the repetition of bodily movement’ (Yuasa, 1993, p. 13). I sometimes refer to my approach to playing as ‘catching a wave,’ acknowledging that at these moments, the wisdom of the body is foremost (Ray, 2008, chapter 20), and I experience a glimmer of what Yuasa calls, drawing on Buddhist philosophy, ‘no-mind’:

‘In the state of no-mind, the subjective-objective ambiguity between one’s mind and body disappears, and the body as an object is made completely subjective. The body already loses that object-like weightiness which resists the mind’s function as subject; the body acts by passively receiving the power of creative intuition brimming forth from the dimension that transcends the dimensions of everyday self-consciousness.’ (Yuasa, 1987, p. 108)

William Parker, echoing (appropriately enough) the Zen parable of the empty cup (Reps, 1991, p. 17), describes improvisation ‘not [as] the art of making up, [but] the art of emptying oneself of all preset ideas’ (Parker & Budhill, 2007, p. 100). The Glues Browling project has fostered the conditions for such an emptying, allowing me to catch glimpses beyond the veil of conscious design.

I try to employ a similar tactic in my teaching. I recall a couple of occasions during orchestral rehearsals, working on challenging passages, when the conductor, rather than delve into various technical suggestions or alternative approaches to practising, would ask us simply to play it again but better. As if by magic, it always worked. Aside from presenting a potential threat to any pedagogue’s sense of self-importance, this points towards the primacy of psychology in much of music making. It was as though the request to do something better both sharpened the mind and imparted a sense of evident simplicity, delivered with trust and faith. Of course we could manage it. Why had we thought it so difficult before? Things suddenly became effortless. Now when students of mine encounter material that seems to get away from them, I invite them to realise the passage in their psychic body, to play the section through in exactly the way they want to, but inwardly. When they return to the physical plane, they almost always flow straight through like a breeze. They didn’t suddenly become more technically proficient; they simply stopped getting in their own way, ‘emptying [themself] of all preset ideas’ (Ibid.). To be able to access this place of effortlessness, however, one must have demonstrated a certain level of commitment to their practice, as I discuss below.

We come finally to the Knight of Pentacles, representing the earth element, grounding us in the beauty of the body and the everyday: ‘[t]he very mundaneness of day-to-day life ensures, by a kind of law of reciprocity, that such things possess a greater ‘magic’ than the more immediate attractions of the other elements’ (Pollack, 1997, p. 233). What is music if not magic of the everyday?

This Knight represents diligence, focus, stability, responsibility, patience (Valenza, 2016, p. 293; Horn, 2024, p. 104; Pollack, 1997, p. 238); all qualities that serve us well in any pursuit. However, there is a danger of fixity: ‘deeply grounded in, yet unaware of, the magic beneath him, [the Knight of Pentacles] identifies himself with his functions’ (Pollack, 1997, p. 238). For as long as I can remember, I have found it easy to commit to a practice (whether that be learning old-time songs from a harmonica instruction manual or working my way through lists of must-read English literature), remaining steadfast for lengthy stints. There have been very few periods in my adult life in which aspects of my daily routine haven’t revolved around some committed practice or other. This drive has allowed me to go deep into an odd assortment of interests, to develop skills for which there are no shortcuts, and to experience the unbounded joy of focussed curiosity.

However, there has often been a very fine line separating my self-discipline from compulsive behaviour, and at times I’ve tipped over the threshold. A day off, for legitimate or uncontrollable reasons, can be experienced as a failure, a blow to self-esteem, as though my worth is tallied up moment to moment on a cosmic score board and that others will soon soar ahead of me, thus confirming my insignificance[2]. I am certain that many, if not most, people will be familiar with such a pattern of thinking, if not in themselves, then in those close to them.

Approaching now the back end of a third decade of intense involvement with musicking, many things have, of course, changed. I have grown up, more mature, less impulsive, more experienced. Of greater significance has been a steadily emerging sense of spiritual clarity. As with my interest in music, this didn’t appear from nowhere. For a brief period as a teenager, I was convinced that I wanted to enter the clergy of the Christian church. I have since wandered far, but along what I see as the same path. Whatever one’s beliefs, I share William Parker’s conviction that the creation of music is a sacred act, and that a musician must put humanity before music, channelling a selfless compassion towards the healing of others (Parker & Budhill, 2007, p. 16). To frame it another way, Sangharakshita posits that ‘art in all its forms, religion in all its forms, and so on, are all means for evolution, for the Higher Evolution of humanity, and that by participating in them… we ourselves are evolving, and that others too are evolving’ (Sangharakshita, Lecture 97: Transcending the Human Predicament, 1971, p. 9). To understand artistic practice as one of cultivating compassion and of helping to lead oneself and others towards a higher stage of human spiritual evolution, we can begin to undo the solipsistic knots of egoic obsession, discovering instead ‘the emptiness out of which comes true freedom, true creativity’ (Chayat, 1996, p. 51). This freedom leads to what shakuhachi player Ray Brooks calls a ‘discipline that isn’t motivated by success or failure and where effort and hard work are their own reward and come naturally, without resistance’ (Brooks, 2000, p. 231).

In tandem with this shifting outlook has arisen a focus on the body as the primary locus of musicking. In reductive and coarse terms, I consider my period of Western classical study as eye-centred; jazz study as ear-centred; and free improvisation and shakuhachi study as body-centred. Much of my time as an aspiring classical violinist was spent deciphering and interpreting written material. As I became more familiar with the modes and sites of jazz practice, my attention shifted to the aural, massively expanding my sonic universe. In more recent years, I have begun to (re)connect to my body, learning to trust that oftentimes ‘my body knows what to play much better than I myself’ (Ferrett, Hayden, & Thomas, 2018, p. 100). A brief course of body psychotherapy in my early twenties left me confused and shaken. How was I to understand such questions as ‘where do you feel it in your body?’ I was utterly disconnected, but equally unaware of that disconnect. A sustained practice of meditation, amongst other things, has grounded me in the physical. Reginald A. Ray, Buddhist teacher and advocate of somatic meditation techniques, summarises the experience of re-embodiment thusly:

‘Our ego, our self-apparatus, our disembodied life, is like a suit of armor that is way too small. We are in there, we are being constricted to death, and we are suffocating, drowning in our own psychological and spiritual vomit. Then somebody says, “You know, if you follow the spiritual path, you can get out of this.” So we try it out, we practice, and the suit of armor starts falling off. And, of course, then we see what the process is really like—we begin to feel like a raw nerve. We feel very vulnerable. But, on the other hand, we feel the fresh air against our skin, the warmth of the sunlight, the cleansing of the pure rain. We finally begin to feel free.’ (Ray, 2008, chapter 34)

Trusting the body to lead in improvisation can be exhilarating. In recent journal entries on my solo practice, the following excerpts allude to this particular joy: ‘a real physical release… the body knows what to do (the feeling is limited to a small physical window, outside of which the character is less successful)… a total physical abandon… letting the body and the instrument guide this gradual disintegration… embracing the rhythmical interruption which flows out of my loosening hold on the equal strikes.’

This emphasis on the body has been bolstered by studies rooted in Japanese pedagogical attitudes, about which shakuhachi player Bruno Deschênes explains that ‘the model of teaching and learning traditional arts is based on the body, avoiding intellectual procrastination…’ (Deschênes, 2018, p. 284). When the ideological shackles tethering our modes of play to predefined conceptual windows are removed, when we enter a space in which we feel liberated, as drummer and community music leader John Stevens put it, to ‘scribble’ with the body (Stevens, 2007, p. 91), there’s no telling what surprises we might find. No two bodies being identical, such a process inevitably cultivates the development of a singular voice. In elegant paradox, Fischlin, Heble, and Lipsitz identify how this personal growth fosters communal cohesion through the recognition of difference:

‘The French critic Alexandre Pierrepont explains in his liner notes to Transatlantic Visions that “improvisation is the other. It is becoming someone, the other that we are—not the one standing next to you, but the other here awakened by the one who is passing by, passing through you.” This view of improvisation necessitates the other, who is in fact standing beside you playing, because the key to self is found through how it encounters difference.’ (Fischlin, Heble, & Lipsitz, 2013, p. 70, emphasis added)

The body is a pathway to honouring the primacy of community.

In his 1993 book ‘The Body, Self-Cultivation, and Ki-Energy,’ Yuasa identifies this movement from body to mind as essential rather than discretionary:

‘…the tradition of Eastern self-cultivation places importance on entering the mind from the body or form. That is, it attempts to train the mind by training the body. Consequently, the mind is not simply consciousness nor is it constant and unchangeable, but rather it is that which is transformed through training the body.’ (Yuasa, 1993, p. 26)

It is this transformation of the mind by way of the body, leading, as I have concluded above, to an understanding of self through others, that I now believe to be the beating heart of music making. A commitment to this transformation, inevitably privileging process over outcome, runs counter to the capitalist demand for commodification, drawing music through the bodies of practitioners back into the communal and societal bodies. Yuasa posits that ‘cultivation is to impose on one’s own body-mind stricter constraints than are the norms of secular, ordinary experience, so as to reach a life beyond that which is led by the average person’ (Yuasa, 1987, p. 98). Perhaps we can dream bigger, envisioning a global life beyond the average, realised through a societal shift in how we understand and practice music.

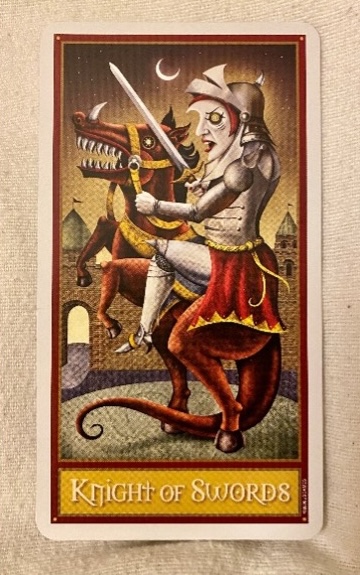

Conspicuous in its absence is the Knight of Swords. The suit of air; fleet, swift, changeable, typically connected to thought and reason, ideas, concepts, and so on. In the Deviant Moon deck, the Knight is on the cusp of racing through the open gates of the city, looking outward, reckless, daring, impulsive. Valenza says about this character, ‘[h]is allegiance is to himself, and his ego knows no boundary. Though the Knight seeks to be free of his limitations, his spirit will always be encased in the armor he wears. Forged by vanity, it glistens with conceited pride’ (Valenza, 2016, p. 119).

As much as I would like to say that I am unfamiliar with vanity or pride, to do so would be to grossly misrepresent the truth. I have indeed acted in ways solely motivated by the desire for praise. I have felt bitterness at not receiving the acclaim I believe is rightly mine. I have turned away from others for fear that their talent eclipses mine. Here is ego in all its shining blindness.

The absence of Swords is an invitation to cast off the protective armour of the ego and ‘to wash away everything and become a beginner over and over and over again’ (Chayat, 1996, p. 78). I have come a long way, but really, I haven’t gone anywhere at all. As the Heart Sutra of Buddhist scripture so succinctly articulates, ‘attainment too is emptiness’ (Emptiness and the Heart Sutra, n.d.)

Providing an auspicious thread between Buddhism and the Tarot via the Fool (card 0), Tibetan Buddhist master Chögyam Trungpa offers humbling words for when air threatens to inflate our ego:

‘…by sitting and meditating we acknowledge that we are fools, which is an extraordinarily powerful and necessary measure. We begin as fools… We must be willing to be completely ordinary people, which means accepting ourselves as we are without trying to become greater, purer, more spiritual, more insightful. If we can accept our imperfections as they are, quite ordinarily, then we can use them as part of the path.’ (Trungpa, 1976, p. 44)

For a long portion of my life as a musician, the message I internalised was that I was seeking greatness, recognition, prowess. As indicated above, this has created psychological and spiritual conflict. Understanding and unpicking these tangles has slowly usurped attainment as a driving force in my practice, representing a move into a different stage of the Fool’s journey.

For Sangharakshita, drawing on the wisdom of the White Lotus Sutra, ‘the human condition is one of alienation. Man is alienated from his own higher self, from his own better nature… He’s alienated from his own highest potentialities, alienated from truth, alienated from reality’ (Sangharakshita, Lecture 98: The Myth of the Return Journey, 1971, p. 6). Returning to his earlier words, each of us walks the path of spiritual development in different ways:

‘…we start off with so many different temperaments, with so many different personal idiosyncrasies, and we’re naturally attracted at the beginning by different things. But gradually a change takes place. As we get more and more deeply into our chosen subject, we understand it better. We understand its true nature. We become aware of what it is doing to us. We realize that we are changing, that we are developing, through our participation in this particular subject, through our interest in it, our preoccupation with it. And we find that our idiosyncrasies of temperament, even those which led us to that particular subject, are gradually being resolved. And in the end we realize that art in all its forms, religion in all its forms, and so on, are all means for evolution, for the Higher Evolution of humanity, and that by participating in them, by participating in any of them, we ourselves are evolving, and that others too are evolving, even though their initial approach and their special preoccupation is different from our own, we realize that we’re all evolving together, we’re participating in the same general process, the process of the Higher Evolution of man, or the process of Cosmic Enlightenment.’ (Sangharakshita, Lecture 97: Transcending the Human Predicament, 1971, p. 8)

For many years, I believed that it was mind and reason that were guiding my artistic growth. I was unable to see that my mind was in fact a passenger in the vehicle of the grounded, embodied, communally centred musical way of being. Rather than a quest for technical and intellectual mastery of one’s tradition, I am now beginning to see music as a pathway to the development of the four Buddhist Brahma-vihāras: loving-kindness, compassion, equanimity, and sympathetic joy. These are qualities which can be explained but only truly understood once they are experienced through one’s whole being. In this sense, perhaps the mind (swords/air) can lead us to the water, but we need the body (pentacles/earth), the emotions (cups/water), and the intuition (wands/fire) to remember how to swim.

‘…in the world of the water, there are no signs… when the wave touches her true nature—which is water—all her complexes will cease, and she will transcend birth and death.’ (Hanh, 2008, chapter 17)

John Garner

[1] I still work regularly with violinist Marie Schreer in the duo Mainly Two, focussing on new works for two violins, as well as improvisation.

[2] Buddhist teacher and author Ethan Nichtern identifies insignificance as one of the ‘eight worldly winds,’ the twin of fame: ‘whenever we become attached to some plateau of stillness or ease, these experiences can knock us off balance’ (Nichtern, 2024, introduction).

References

Blackstone, J. (2023). The Fullness of the Ground: a Guide to Embodied Awakening. Boulder, CO: Sounds True.

Brooks, R. (2000). Blowing Zen: Finding an Authentic Life. Tiburon, California: HJ Kramer Inc.

brown, a. m. (2017). Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. EBSCOhost.

Butler, O. E. (2014). Parable of the Sower. London: Headline Publishing Group.

Chayat, R. S. (Ed.). (1996). Subtle Sound: The Zen Teachings of Maurine Stuart. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Deschênes, B. (2018). Bi-musicality or Transmusicality: The Viewpoint of a Non-Japanese Shakuhachi Player. International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 49(2), 275-294.

Emptiness and the Heart Sutra. (n.d.). Retrieved July 30, 2024, from The Buddhist Centre: https://thebuddhistcentre.com/stories/toolkit/heart-sutra-emptiness/

Ferrett, D., Hayden, B., & Thomas, G. (2018). weaving intuitive illegitimate improvisation. Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, 14(1), 90-109.

Fischlin, D., Heble, A., & Lipsitz, G. (2013). The Fierce Urgency of Now: Improvisation, Rights, and the Ethics of Cocreation. Duke University Press.

Garner, J. (2022, October 31). Centrifugal Apotheosis: Allan Holdsworth’s Fluid Dynamics. Retrieved from John Garner: https://johngarner.co.uk/scribblings/centrifugal-apotheosis

Hanh, T. N. (2008). The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching. Ebury Publishing.

Horn, K. V. (2024). The Inner Tarot: A Modern Approach to Self-Compassion & Empowered Healing Using the Tarot.London: Piatkus.

Lee, S. (2020). Be Water, My Friend: The True Teachings of Bruce Lee. London: Penguin Random House UK.

Lewis, G. E. (1996). Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives. Black Music Research Journal, 22, 91-122.

Nichtern, E. (2024). Confidence: Holding Your Seat through Life’s Eight Worldly Winds. California: New World Library.

Parker, W., & Budhill, D. (2007). who own’s music? Cologne: buddy’s knife jazzedition.

Pollack, R. (1997). Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Thorsons.

Ray, R. A. (2008). Touching Enlightenment: Finding Realization in the Body. Boulder: Sounds True, Inc.

Reps, P. (1991). Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. (P. Reps, & N. Senzaki, Trans.) London: Penguin Arkana.

Sangharakshita. (1971). Lecture 97: Transcending the Human Predicament. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from free buddhist audio: https://www.freebuddhistaudio.com/texts/lecturetexts/097_Transcending_the_Human_Predicament.pdf

Sangharakshita. (1971). Lecture 98: The Myth of the Return Journey. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from free buddhist audio: https://www.freebuddhistaudio.com/texts/lecturetexts/098_The_Myth_of_the_Return_Journey.pdf

Sangharakshita. (2010). The Bodhisattva Ideal: Wisdom and Compassion in Buddhism. Cambridge: Windhorse Publications Ltd.

Stevens, J. (2007). Search & Reflect: a Music Workshop Handbook. CALIGRAVING LTD.

Trungpa, C. (1976). The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Uchiyama, K., & Okumura, S. (2014). The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Valenza, P. (2016). Deviant Moon Tarot. Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems, Inc.

Yuasa, Y. (1987). The Body: Toward an Eastern Mind-Body Theory. (T. P. Kasulis, Ed., N. Shigenori, & T. P. Kasulis, Trans.) New York: State University of New York Press.

Yuasa, Y. (1993). The Body, Self-Cultivation, and Ki-Energy. (S. Nagatomo, & M. S. Hull, Trans.) Albany: State University of New York Press.

Yunkaporta, T. (2019). Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company.