In the autumn of 2021, in the haze of a world reeling from the shock of a global pandemic, jazz faculty members at Leeds Conservatoire, myself amongst them, were offered a small bursary towards continuing professional development. After one lesson with the extraordinary Indian violinist Kala Ramnath, I decided to try my hand at something else entirely. Thus it was that my relationship with the Japanese bamboo flute, the shakuhachi (尺八), began, not altogether surprising considering my longtime fascination with the country and its rich culture. I chose as teacher grandmaster Cornelius Shinzen Boots, a player in the lineage of Watazumido. Like me, Boots arrived at the bamboo via Western classical and jazz music, and so, from a distance, he seemed something of a kindred spirit who would be well placed to ferry me across this musical, cultural, and spiritual membrane (and I wasn’t wrong).

Reflecting upon the currents in my musical and spiritual practice effected by the appearance of the shakuhachi, I called on the tarot for inspiration (as an aside, there’s a pleasing symmetry in the fact of the approximately contemporaneous emergence of the instrument as we know it today and the tarrochi cards of Italy). For any on the cusp of turning away at the mere mention of the cards, rest assured that there is no divination here, only introspection (no intentional divination, at least). My favoured deck is Patrick Valenza’s ‘Deviant Moon’ — stunning designs and highly intuitive to read. I’m indebted to Valenza, Kate Van Horn, and John Pope for what little I understand about reading the cards.

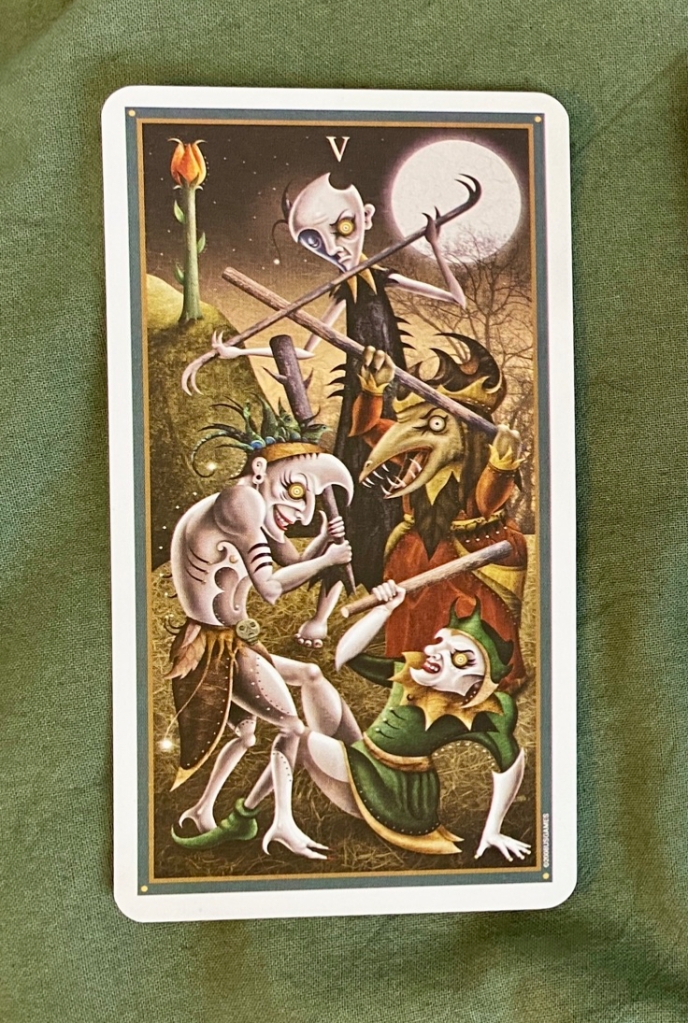

Up first, the Five of Wands: a difficult place to start. Strife, division, trauma even, and yet in the Valenza design, there sits a lone (bamboo?) wand growing happily from a hilltop in the distance, apart from the violence. For many years now, I have agonised about my way of being a musician in the world, the sociocultural and political significances of the musics I play, the hegemonic mechanisms of the industries within which I work (Prévost, 1995; Small, 1998), all of which is a story for another day. Suffice it to say that the shakuhachi has emerged from this disarray as a beacon of sorts. The struggle in the foreground of the card could signify competition, in my opinion functioning most often as a poison circulating through certain sites of modern-day British musicking and musical pedagogy. The shakuhachi doesn’t belong to this world of attainment and one-upmanship which has characterised so much of my experience over three decades as a musician (of course, the instrument is no more immune to such trends than any other; I am simply referring here to my relationship with the practice). Whereas the four figures locked in combat represent perpetual and irreconcilable tension, the fifth wand develops in its own time, peaceful and patient, young leaves sprouting from the stem (other avenues of inquiry yet to come?).

Second, from the major arcana, comes Temperance. Of all the cards that could be said to encapsulate the spirit of the shakuhachi, this one would be a serious contender. The shakuhachi doesn’t (theoretically) belong to the world of virtuosity, technical prowess, innovative interpretation, celebrated individual artistry (economic machinery will, nevertheless, often find a way to foreground material and commercial success). It is a slow practice, a privileging of the body and form, ‘a process-oriented exercise in spirituality, in which the sound product is not as important as the physical and mental state of the performer’ (Lee, n.d., p. 135). In my teacher Boots’ framework, all explorations of the instrument, all technical, aural, stylistic, interpretative developments, are designed to deepen the player’s connection to ro, the fundamental tone of the bamboo (verticality over horizontality (McDermott, 2023)). Whereas open-strings on the violin are something of a spectre for students (the threat of an enforced return to open-string practice always looming, even at higher study), ro is the lifeblood of the way of the shakuhachi. So extraordinarily different is this from the repertoire-based pursuits of the Western classical violin, or the intricate improvisational underpinnings of jazz in its myriad emanations, that a radical restructuring of the basic ground of musical being is also necessary, in the same way that a Buddhist contemplative practice can pose a serious challenge to the principles and demands of contemporary life in the Global North.

Temperance doesn’t belong to showmanship, nor to attainment-oriented learning models. As certain Buddhist teachings would have it, how can you attain something you’ve already got (Buddha Nature)?

Writing on the thorny topic of cultural appropriation, Bruno Deschênes considers the concepts of ‘de-identification’ and ‘re-identification’ (Deschênes, 2018). Appropriation happens when one intends only to take something for oneself, with a view ultimately to profiting from that theft. When one is willing to be changed (‘vulnerable enough to be changed’ (brown, 2017, Creating More Possibilities section)), to let go of parts of oneself (to de-identify), ‘to partially put aside… some of the musical training he has received from an early age (which can be extremely difficult to do, especially if it is considered a kind of musical and cultural truth)’ (Deschênes, 2018, p. 285), then there is the possibility of an ‘intermingling from which a community can take form’ (Deschênes, 2022, p. 70), something which grows and blooms in deep time (the fifth wand). This is not a process of learning that seeks emancipation from society, to be raised up, celebrated, but rather a process intended to thicken relationship, to generate connection, to open the heart into a life led by compassion. Temperance as pathway, shakuhachi as compass. ‘The goal of Japanese artistic training is not the perfection of an art object as an end in itself, but the development of the self as a never-ending, lifelong process’ (Keister, 2004, p. 104). Although universes apart stylistically and culturally, this recalls legendary AACM musician and theorist George Lewis’ assertion that ‘[i]n performances of improvised music, the possibility of internalizing alternative value systems is implicit from the start’ (Lewis, 1996, p. 110).

To finish, the Ten of Cups, a card of celebration, affection, love, interbeing. In Valenza’s design, all the suits are represented, a totality. Nothing is permanent, of course, but for now there is space to rest and experience the joy of being, being whole in oneself and with others. A gibbous, dazzling moon (the clear light?), with ten cups afloat in the sky, representing the body of emotional wellbeing, the wellspring of abundance. The card speaks to the Buddhist origins of the instrument. The Boddhisattva is committed to saving all beings, through lifetime after lifetime after lifetime (nobody is free until we are all free). The shakuhachi is intended, if the mythology is to be believed (and even if the mythology is fabricated, it saturates the contemporary philosophy of the practice), as a tool for spiritual insight and grounding, for transcending the ego, for remembering interbeing through the portal of sound. The breath is given voice through the (largely unworked, raw) bamboo. Whereas in Western classical music and other traditions, we might expect students to graduate to more complex instruments (think of the idea of the recorder as a preparatory tool), here we can see that a master might relinquish design features. In a koan-like sense, perhaps the master plays the shakuhachi-less shakuhachi, before finally vanishing herself.

In summary, the shakuhachi entered my life during a time of artistic uncertainty, and has offered a radically different way of being, both musically and spiritually. Everything need not be fast, innovative, impressive, productive, virtuosic, elevated. There is a beauty in temperance, patience, repetition, in taking the scenic route, slow, open to surprise, interruptions, unencumbered by what has been or what might come. Existing, practising, in this way, we can return to a state of joyful and grounded curiosity, awakened to the glory of others through the deeper truths of ourselves: ‘[i]n reaching the most personal core of our own being, we find our oneness with all other beings’ (Blackstone, 2023, p. 27), ‘the individual as a part of global humanity’ (Lewis, 1996, p. 110). In these early days of my life as a disciple of the bamboo, I can say for certain that I am filled to the brim with gratitude.

John Garner

Works Cited

Blackstone, J. (2023). The Fullness of the Ground: a Guide to Embodied Awakening. Boulder, CO: Sounds True.

brown, a. m. (2017). Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. EBSCOhost.

Deschênes, B. (2018). Bi-musicality or Transmusicality: The Viewpoint of a Non-Japanese Shakuhachi Player. International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 49(2), 275-294.

Deschênes, B. (2022). World Music: Appropriation or Transpropriation. BAMBOO – The Newsletter of the European Shakuhachi Society, 68-75.

Keister, J. (2004). The Shakuhachi as Spiritual Tool: A Japanese Buddhist Instrument in the West. Asian Music, 35(2), 99-131.

Lee, R. K. (n.d.). The Technology of Notation Systems and Implications of Change in the Shakuhachi Tradition of Japan. In D. E. Mayers (Ed.), The Annals of The International Shakuhachi Society, Volume 1 (pp. 133-138). Wadhurst, Sussex: The International Shakuhachi Society.

Lewis, G. E. (1996). Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives. Black Music Research Journal, 22, 91-122.

McDermott, M. R. (2023, April 27). Breathing Bamboo: Cornelius Boots (No. 32) [Audio podcast episode]. Sounds of SAND. Science and Nonduality (SAND). Retrieved from https://we.scienceandnonduality.com/podcasts/sounds-of-sand/episodes/2147925760

Prévost, E. (1995). No Sound Is Innocent. Harlow: Copula.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.