A film by Case Esparros – with score by Aaron Dilloway

An absence begins

“Every so often the pulse of the underground gets resurrected.

This is one of those moments.”

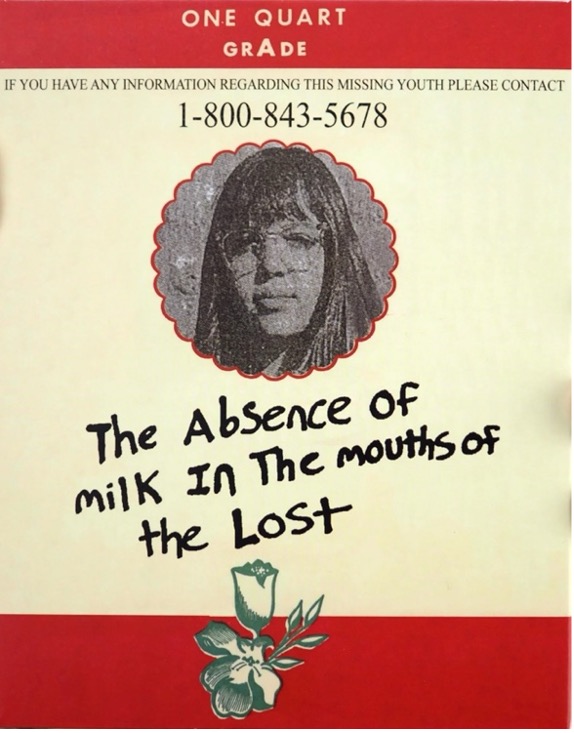

These are the words used by cult director John Waters to describe Case Esparros’ second feature length film, the poetically titled ‘The Absence Of Milk In The Mouths Of The Lost’. Released in 2023 and now available on Blu-ray, it follows on from Esparros’ 2019 film ‘King Baby’. But whereas his dreamy debut was a second coming of Christ story about hope and loss of innocence, any sense of optimism is harder to gleam in this latest statement from the underground filmmaker.

The set-up for The Absence Of Milk In The Mouths Of The Lost seems deceptively simple. Maria, a single mother tenderly played by Hannah Weir, is severely struggling with the enduring grief for her missing child – one of several children who have vanished from a nameless, everywhere, town. It is the one-year anniversary since a now 11-year-old Jessica suddenly disappeared from one of their regularly visits together to the local park.

“I watch the clouds part this morning

and a couple of tears fell out of them

so I’m happy they can feel something,

I can’t say I have been.”

A never-ending cycle of grief

Maria is not coping with managing her unending trauma and via fragmented shards of action and narration we witness her reaching out to talk to Jessica in the present: “Right now and every day I want you to be great. Things right now are scary and they will continue to be scary but I’m watching over you. I may not be around but I love you more than you could ever know.” Weir plays Maria with a transparency where her soul is exposed and we can see how haunted she has become. Maria is one of several other mothers who are trying to cope with their respective loss coupled with a suburban, Sylvia Plath-like boredom mixed depression. The inhabits of the town are living in the shadow of David Lynch’s American Dream filtered through the surreal dark humour of Harmony Korine.

Maria appears to be a thematic echo to Gena Rowland’s apprehensive and quiet turn of character in Cassavetes’ ‘A Woman Under the Influence’. She visits the park she used to take her daughter and sits and watches other children play. When she visits a couple of her few friends, they comment on how detached she is. Maria is a mother stuck in a loop. One where she baths in dirty water, has forgotten how to eat, how to sleep and how to exist at all. Living alone inside her rundown tired house, which doesn’t have the traditional white picket fence like her neighbours, Maria is surrounded by icons of Jessica’s childhood gathering dust like in a museum. Grainy VHS footage is efficiently used to flashback to when Jessica shared happier times at home with her mother on her birthday and at the park. “Today all I ask of you Jessica is to have a special birthday”.

This cycle of grief is an energy that her neighbourhood milkman mysteriously begins to feel a strong connection with, having what looks to be a shrine to Maria and newspaper clippings of the other missing children on the wall at his home, alongside a collection of mannequins and a scrying bowl of milk. Meanwhile, somewhere away from town, the group of missing children sleep in a barn and put on an Alice in Wonderland style birthday tea party for Jessica while trying to avoid a group of human-like demons.

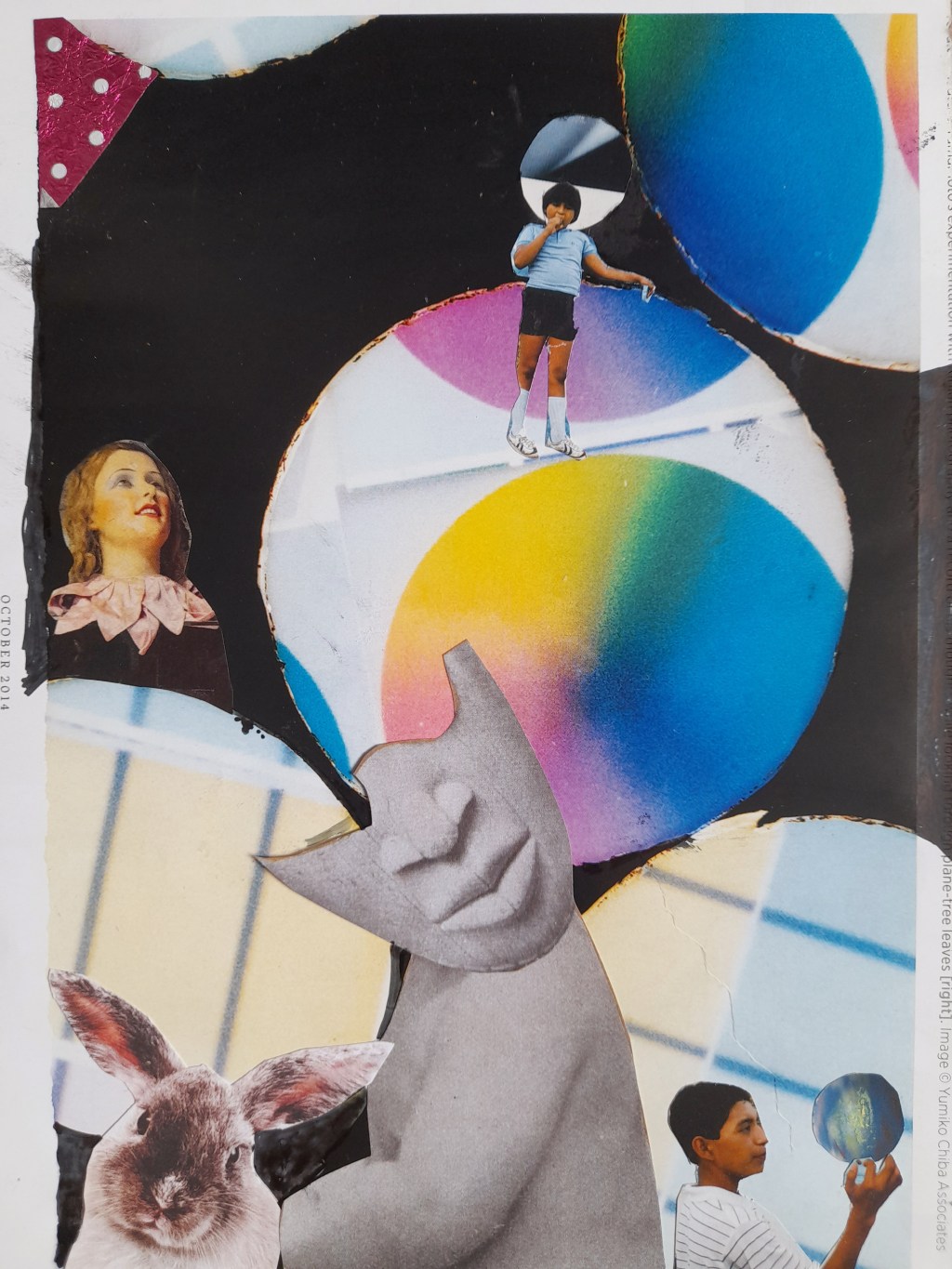

The Absence Of Milk In The Mouths Of The Lost inhabits a daring indie spirit. Shot mainly in San Pedro, California, the film shares a thematic universe with another outsider artist, American writer, novelist and mixed media collagist Henry Darger, specifically his posthumously discovered epic fantasy novel ‘The Story of the Vivian Girls…’ in terms of its sprawling illustrated tale of missing children rebelling against their captors in a battle of good versus evil. The film explores the effects of trauma when combined with imagination and magic realism like Del Toro’s ‘Pans Labyrinth.’

The missing children in the film seem to be living out their days in some rural Neverland nursery rhyme limbo space. Wearing Venetian style masks, their identities are hidden and stuck in time. It is a form of dress up, children playing make believe like the Lost Boys – although here all the missing children are girls, possibly an allusion to Darger’s Vivian Girls. But what do we believe? Are these missing children still living in this realm, or ghosts drifting away from reality? Could there be a guardian angel watching over them? Armed with bows and other makeshift weapons they are not afraid to defend themselves from their encircling demons, to fight off pain and to try to maintain their innocence.

When they do appear, the physical embodiment of the demons has an endearing DIY quality to them, complete with white body paint, stuck on tiny horns, puffing cigars and red polka dot boxer shorts. Living in rusty RVs and seen silently picking the fluff out of a teddy bear or barbecuing steaks, they are the type of surreal characters that might be found in the experimental films and photography of Jack Smith, 1963’s ‘Normal Love’ for instance. Sharing a similar, albeit more cartoon-like quality, creepiness to the “Got a Light?” shadows creatures that emerged in Part 8 of ‘Twin Peaks: The Return’, these demons – almost spirit bulls – could be a physical signifier of the negative energy that emerges from out of loss and the ultimate force the children want to keep at bay.

In Greek mythology, Algea (which mean ‘pain and grief’) was used by the poet Hesiod as the personification of both physical and mental pain. The Alegea were the bringers of weeping and tears and were represented as the children of Eris, the goddess of strife and discord. Perhaps the demons in ‘The Absence…’ are a version of the Alegea, brought to life from the parent’s combined grief over their missing children and metaphorical loss of identity and of the heart as well.

Narrative cohesion is of less importance in an abstract film like this. The focus is on imagery. A cow gives birth. The milkman repeats his delivery round. Maria and the other mothers are shown in silent acts of distress inside their domestic cages. The children play act as adults in the forest. Every scene is a painting or photograph and the film is an incomplete assemblage of these weaved together. A sense of absence extends far beyond the missing children of this town, into the absence of connecting scenes, back stories and dialogue. Even after repeated viewings, there are several photos missing from this town’s hypothetical photo album, with gaps left in the story for the audience to try to fill in.

There are a few moments throughout where the slow, deliberate pace is disrupted by Esparros introducing Stan Brakhage ‘Dog Star Man’ style collage sections created from blood and milk paintings on 16mm film – all rapidly cut distressed and scratched textures. This expressive technique is very efficient in representing the grief spirals of the mothers. Their narration, which has been synthesised, pitched up to resemble an alien or insectoid voice (a technique used in Esparros’ 2016 short film ‘Herbert’ (a story also concerned with the loss of loved ones), takes us further away from reality, into another realm of psychological disorder. One mother aimlessly knits as she soliloquies. Another confesses to her doctor about her pain. Other dreamy sequences are dropped into the main narrative to show how life is definitely not all milk and cookies anymore for these mothers. “Tonight your bowl of ice cream is left out in case you want to join me for desert”.

Meet the milkman

Reclusive musician Gary Wilson plays a version of himself as the aforementioned milkman – a Darger-esque collector and mysterious character who is more metaphor than man. Described by Esparros as “the average American man with an average American job,” Wilson sees the milkman as being “there to provide comic relief, comfort, and milk to the lost.”

Set in a frozen-in-time 1950s Americana nostalgia (much like Wilson’s music), where milk was more commonly delivered and photos of missing children were found on the back of milk cartons, the film shares a spirit with an episode from ‘the Twilight Zone’. Milk is a symbol of abundance, food of the gods, a simplified spiritual knowledge. Milk is mother, a connection to a child. A milkman delivers fresh milk and takes away empty bottles. From the grieving parents to the life cycle of dairy cows which play a prominent part in establishing the theme, giving birth only to be separated from their young, milk is deeply connected with life itself. “You never outgrow your need for Milk!”

There are moments when the milkman adapts the classic milkman costume. When he gaffer tapes plastic around his head and dons a black wig and lipstick it ties in with the symbolism of the mannequins that inhabits his basement. As well as being a method to hide away from the world, there is a desire for an unattainable ideal; an attempt to fix a disconnected sense of identity. When the milkman places a white plastic bag over his head, he resembles the Invisible Man or a classic bedsheet ghost complete with milkman’s hat and Wilson’s signature white plastic cat’s-eye sunglasses. As well as being a nod to Wilson’s inclination for wearing plastic bags and wigs as part of his performance art, this shows the milkmen as another shapeshifter, another fractured soul. Is he a seer with supernatural insight? An angel or a ‘visitor from heaven’ as seen written on a page in a colouring book that Maria clings to? An empathetic carrier of the mother’s grief between realms? A Virgil-like figure guiding a pathway across the Styx, connecting the land of the living and the dead? Or could the milkman be a sin-eater trying to consume the sins of the lost?

Namechecked by Beck in his hit 1996 single ‘Where It’s At’ – “Passin’ the dutchie from coast to coast/like my man Gary Wilson rocks the most,” the character of the milkmen is played by outsider musician Wilson with eerie intensity and an aesthetic all of his own. As a Beatles-obsessed youngster, he watched them play live at Shea Stadium, Wilson’s music would grow increasingly experimental after discovering Varese, Bartok and Schoenberg. But his biggest influence became the work of John Cage. Gathering a passion for Cage’s work, a young Wilson sought out the composer after finding his number in the New York phone book, which led to him being invited to Cage’s home to critique his burgeoning classical compositions together. If what you are doing “doesn’t irritate people, you aren’t doing your job,” was the advice Cage passed on to a then teenage Wilson, who still sees Cage as “my biggest hero.”

It was Wilson’s 1977’s debut album ‘You Think You Really Know Me’ which really spoke to a teenage Esparros and helped him through a period of identity crisis during high school and it remains a record they will often return to: “it’s powerfully comical, brave, depressing, heartbreaking, infectious, and a painful look into a singular person’s psyche.” The writer and director saw a kinship and artistic connection with the musician and would later find the opportunity to befriend Wilson. In fact, the character of the milkman was written as a recontextualised version of Wilson and Esparros could not see the film being made without him agreeing to the role. When the milkman dons a wig, to those in the know, this is just Gary Wilson getting ready to go up on stage. Another example of layers within layers, switching between reality and the imaginary.

Gary Wilson’s new wave lounge act would bow out of the public spotlight in 1981 and disappear into two decades of self-imposed exile – echoing a sense of absence that encircles the characters in the film – not returning to the stage until 2002. There was a documentary made about his life, ‘You Think You Really Know Me: The Gary Wilson Story’ and Wilson continues to play live and release new music, with latest album ‘The Marshmallow Man’ released in 2023. He also performed at screenings of the film during its release run.

The repetitive loop of loneliness

Although he scored the preceding short ‘Herbert’, it isn’t Wilson’s music that haunts Esparros’ film, it is the first feature-length score by noise musician and tape manipulator Aaron Dilloway. Already very familiar with the score before viewing the film, it was then left up to my imagination to superimpose visuals in my mind to the unravelling sonic tapestry. The best compliment I can pay is that the score works superbly as an experience all of its own. Full of a queasy sense of dread, it finds Dilloway at his most musically textured, tiptoeing the line between lurching synths and crumbling shards of noise. Working with his favoured 8-track tape loops, Dilloway combines splinters of voice, tape delays and Casio keyboard, to flesh out a melancholic world full of decay, sorrow and tragedy.

Upon viewing the film for the first time with the score firmly embedded to the visuals, I was impressed with how well they complemented each other in tandem with the layered Lynchian sound design. From the uncanny, gentle synth loop textures of ‘Cow Birth Intro’ and the nauseous ebb and flow cut-up of ‘Mother’, to the monotonous and thunderous anxiety that cuts into a nightmarish scream sample in ‘The Missing Children’ and the static-lit drone of ‘Drunken Medley’ incorporating unnerving, reversed synth tones, Dilloway has created one of the best scores in recent times that heightens the emotional intensity of every mise en scene.

Dilloway’s manipulation of tape loops is representative of how characters in the film, from Maria and the other mothers to the missing children, and the milkmen on his rounds to the demons in the woods, are stuck, going back and forth in, as Esparros puts it, the “repetitive loop of loneliness.” And with every loop something might begin to change; there is more disintegration, crumbling, smearing, a breaking down of the sound and the mind.

The chance to be found again

During one of the surreal occasions when a mother speaks out into the ether to their missing child, she says, “if you get home late just make sure to wake me and tell me you’re back.” This is a good way to summarise the experience of watching the Absence of Milk In the Mouths of the Lost – we’re not sure what is real and what is imaginary, what could be a dream or a living nightmare.

“Remember that film we used to watch together? Second star to the right and straight on to morning. I will look for you there,” are some comforting words offered from mother to daughter across the galaxy. These are in fact directions to J.M Barrie‘s Neverland, perhaps suggesting that Maria and Jessica will be reunited in another realm. Barrie wrote that Saturn and Jupiter stood at the ingress of the fantastical Neverland, where Peter Pan and the Lost Boys met mermaids, battled pirates and never grew old. Or in Jessica and the other girl’s case, they met donkeys and chickens and battled demons. On her birthday Jessica is affected by a small dead bird she finds and misses the party put on for her by her friends, realising she is beginning to grow more distant from them. Despite their best efforts the innocence of childhood is slipping away, but mother and daughter will always be connected across time and space.

“Because even if we never see each other again,

you live inside my heart forever. I love you, my Jessica.

Mummy’s got you. Shhhhhhh, Mummy has you.

I will never let you go, my beautiful baby.”

Case Esparros has said that this film was conceived in moments of deepest isolation and he looks back on the process through a massive fog. This is a film so obviously connected to loss in a myriad of ways, but as Esparros writes in the foreword to the booklet that accompanies the physical release, “…whenever you feel lost remember the sun will always come in the morning and you will be granted the chance to be found again.”

The film appropriately closes with a version of Xiu Xiu’s cover of ‘I’ll Fly Away’ playing over handwritten credit titles:

Just a few more weary days and then,

I’ll fly away;

To a land where joy shall never end,

I’ll fly away

The Absence of Milk In the Mouths of the Lost is a raw reminder to always keep looking and remembering, to hold on to love and hope, in order to keep those daily demons everyone experiences at bay. Whether living with grief or depression, or issues linked to identity and self-esteem, remember to look for the second star to the right in the night sky, like Maria and Jessica do.

Ways to watch and support

The Absence of Milk In the Mouths of the Lost was released on Esparros’ own film label Dancing Fireman Pictures. The only way to watch the film online is to pick-up the Blu-ray release, which is a remastered version of the film that got shown on a 10-city roadshow. The collection comes packed with extras including a drunk commentary by Esparros, interviews with the director, Gary Wilson and Aaron Dilloway, a live screening Q&A, and a booklet featuring concept art and behind the scenes photos.

You can support the Absence of Milk In the Mouths of the Lost by purchasing it on Blu-ray from Vinegar Syndrome. It is published by new partner Art Label, which was established by Warren Xian who produced and was first director of photography on the film.

Support Aaron Dilloway’s original score for the film on cassette and digital:

Support Gary Wilson on Bandcamp: https://garywilsonmusic.bandcamp.com/music

Case Esparros on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/caseesparros

Aaron Dilloway on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/medicinestunts

Ryan Hooper