The utility of open-scores – be they graphic, text, or any other abstract medium – lies in their staggering of the reproductive process. Rather than relying on pure symbolism, where a visual object equates, more or less exactly, to a pre-existing movement upon an instrument, the open-score instead asks its interlocuters to explore three related strands: collaboration, interpretation, and intervention. Through such a process, questions arise as to what it means to participate in an artistic collaboration, and how such involvement affects or enhances a participant’s relationship to their broader community (audiences, other players, even their broader social context). Participation is multi-axial: it exists firstly on a spectrum of co-design (how much each participant contributes to the creative whole, and in what manner), and secondly as a performative event wherein any performance can be considered a collaboration with its community, rather than a rendition of an already finished, fully- contoured work.

Participatory works don’t simply entertain an audience, they bilaterally inform (and are informed by) the existing social system in which they are presented.

By and large, open-scores are a poor means of rendering an exact reproduction of a musical idea. Their affordance, therefore, lies not just in a musical outcome, but within the complexity of social function. Despite some composers wishers, scores – even the traditional stave variety – don’t merely replicate an existing work, but are filtered through the being of the performer, a living entity with their own unique way of doing things. Whilst traditional models often seek to diminish the autonomy of the individual by relying on more or less fixed methods of interpretation, open-scores instead enliven a pragmatic question as to whether musical works are truly repeatable at all. Where openness blurs the line between performance and composition, they in essence act as a critique of the sensible – that is, they prioritises the act of making sense above the invocation of a pre-determined made sense, through the construct of a document that only makes sense via its engagement by the community. We might even argue that, in eschewing musical symbolism, open-scores escape the limitations of musical performance altogether, offering a more conceptual space wherein they might just as easily facilitate a painting, a new waying of doing the washing up, or a political debate, as they might a piece of music.

Open-scores resist the determination of their more symbolic cousins, often focusing not on the specific replication of a note or a musical effect, but instead on the physical movement of the body as interacts with an instrument. Such movements, freed from their context, might serve less as ‘ways of playing’ than as ‘ways of being’, actions that can be transposed to a wide variety of situations – be they musical, performative, or mundane. They are, in essence, no longer a means of operating a specific (sonic) tool, but a means of guiding expression. In exploring such a conceptual shift, there is some value in choosing tool that allows for a similarly open-ended exploration of expression. Despite its existing cultural utility, we might argue that in seeking such a vast degree of expression, and in abandoning the requirement for a specific interface or operative rigidity – we could turn to the modular synthesiser.

Whereas a violin (for instance) requires you to bow strings upon a bridge, and across a uniform sounding body (even extended technique is subject to a fair degree of limitation in this regard), the modular synthesiser can be re-arranged for each specific instance of performance. Its signal path is determined entirely by the operator, and its interface can differ even between similarly purposed modules – a reliance on often analogue circuitry and its propensity to be affected by room temperature and variances in the electricity supply of its site often lead to significant variations between ostensibly identical modules. Lacking both a uniform interface and many of the constraints inherent to more traditional instruments (tuning, timbre, range, size of body), the modular synthesiser is somewhat unique in so far it is – ostensibly at least – incredibly difficult to score: even a scientific description of a module’s settings and inter-relation is unlikely to result in the sonic outcome intended. Many existing modular ‘scores’ amount to technical drawings revealing the signal path, or the arrangement of modules, rather than any expressive or musical qualities of the work produced – which feels a little like scoring for the violin by providing instructions for felling a tree. We might go further and argue that the modular synthesizer operates, by definition, in the same philosophical terrain as the open-score. If we can hold certain expectancies as to what an instrument is capable of – the sound-world that it can create – a synthesizer by design eschews this. Theoretically, a modular synthesiser can produce any sound imaginable, by recreating electronically the process that produced such a sound in the first place. Furthermore, the modular synth is comprised of distinct elements whose behaviour can be influenced only by external voltages, carried by the addition of patch cables. The modules of a synthesiser presuppose both operative closure and a productive distance between them – individual modules are brought into a mutual becoming through a governance orchestrated by the addition of an external stimuli. Much like the open-score itself, the modular synthesizer holds a bilateral relation to its community, its performance not a replication of a sonic truth but an active relation between the variety of elements that comprise it.

The affordance of open-scores is that they can embrace the abstract qualities of the participatory exchange – this is not to lazily suggest they cater for the hard to pin down, or the vast fields of the ineffable (although they can), but rather the developmental, the in progress, the unformed. The abstract points, after all, to the freezing of a moment within a process (abstraction), as much as it signifies an opposition to the concrete. With this in mind, open-scores point towards, but don’t reify, physical movements. Rather than referencing any explicit quality of the instrument, these movements reference their position within a wider composition, and yet crucially, are able to avoid defining any specific, immutable qualities of their compositional context.

Lacking the concrete significance of the fixed symbol, the nature of the material that prepends/appends each part of the score is thus undefined, and its interpreter is able to move from one fundamentally malleable station to another as the work progresses. In this way, the potentiality of any section of the score is not bound by specific qualities within the syntax upon which it is based, but is instead shaped by the culmination of decisions the participant has made up to that point. Rather than denoting some specific, pre-arranged technique or sounding, graphic and text scores might instead refer to some undefined quality of its temporal, conceptual, or physical location. In effect, open-scores exist in a state of perpetual collapse, their form always pointing to some unknown aspect just out of sight. They are a type of what Brian Massumi calls “Semblance” – a document more concerned with what isn’t written than what is, the between of its lines. For Massumi, “semblance is a form of inclusion of what exceeds the artefact’s reality”, and the participatory event embodies this: providing only enough of a framework to encourage exploration of the potential beyond both prior experience and the limits of the visual stimuli. Open-scores celebrate, rather than transgress, the distance between the composers original intent and the creative potential invoked by its performers. As Massumi suggests:

You don’t want to just let them stay in their prickly skins. Simply maximising interaction, even maximising self-expression, is not necessarily the way. I think you have to leave creative outs. You have to build in escapes. Drop sinkholes. And I mean build them in – make them imminent to the experience. If the inside folds interactively come out, then fold the whole inside outside interaction in again. Make a vanishing point appear, when the inter- action turns back in on its own Potential, and where that potential appears for itself.

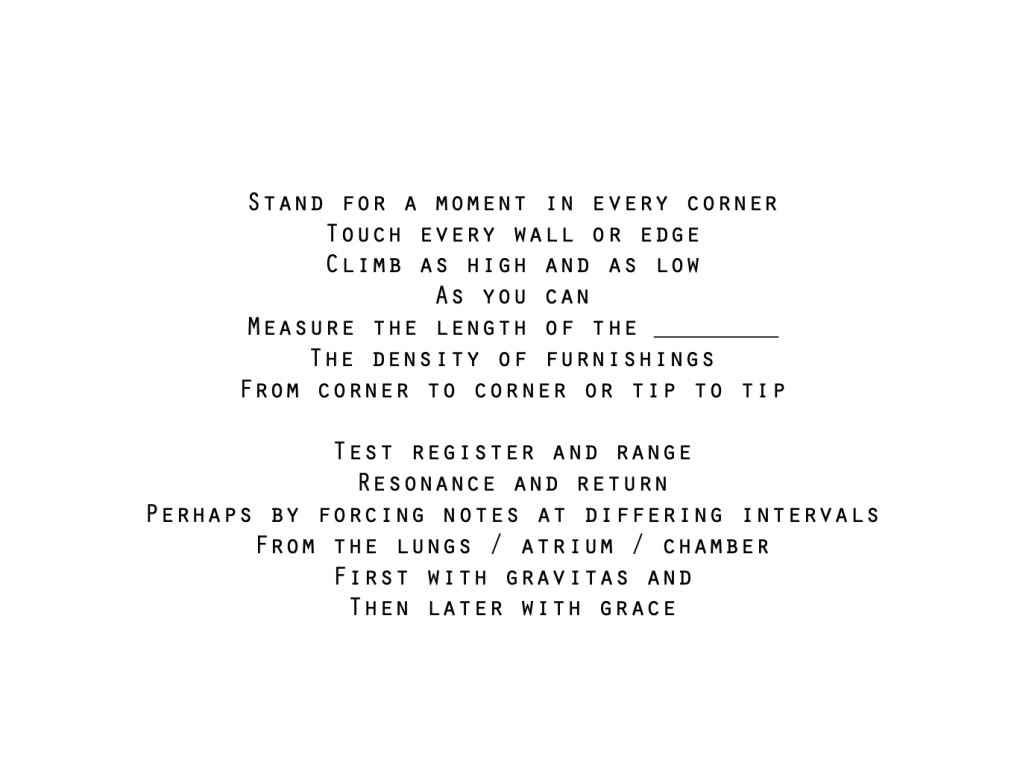

Rather than serving merely as a blueprint for an ideal, finished work, this form of open-ended scoring is more what Lawrence Halprin might consider a methodology for collaboration, acting as “a means of revealing alternatives, of disclosing latent possibilities and the potential for releasing total human resources. They are a way of inviting the unexpected; of expanding consciousness, encouraging spontaneity and interaction; in short the score is a way of allowing the creative process to be ‘natural’” (Halprin, in Lely and Saunder, p.206, 2012). Traces, marks, and shapes, as well as (in the case of text scores) grammatical devices such as polysemy, morphisms and homonyms – allow participants to construct meaning on a moment by moment basis, rather than attempting to point to any overarching sense. Combinations of stimuli might provoke multiple significations, depending on the context. Any sense inherent to the score is made available to the reader only as they move through the conceptual space the imagery and text create. Since the interpretation is open- ended, and the direction of movement (to a greater or lesser degree) autonomous, the sense the text offers is not implicit in the stimuli itself, but co-constructed by its reader.

In this manner, the open-score is developed not as piece of linear writing but as a form of what Tim Ingold calls “line-making”. Drawing from social anthropology, Ingold equates line-making to wayfaring – the unique experience of moving through the world at any specific moment – and sets it in contrast to contemporary ways of reading more readily equated with travelling, which forgo the experience of a journey in favour of a series of destinations.

Scores, like maps, are traditionally objects that have less to do with the conceptual or physical landscape to be traversed, than with arriving at set points, their participants not travellers seeking arrival, but wayfarers on a journey. From a political perspective, scores (and maps) are all too often concerned with lines drawn upon things or through things from above, not lines traced along things with the body, and as such signify “occupation, not habitation” (Ingold, p.85, 2007). Rather than encouraging a community to explore their shared environment, maps, closed-instructions, even stave notation, are ways of appropriating space irrespective of those that dwell there. They are ways of doing that ignore the reality of being, the lives of those involved in their realisation. The ‘line-making’ we find both in wayfaring and in open-scores presumes, in contrast, a symbiotic relationship with its environment, a field in which both subject and object, self and Other, performer and score, are changed not from above but from within, offering in their mutual, co-constructive movements new ways of perceiving and responding to the objects of externality. The lines left by the body as it moves through its community, the performer as they move through a score, their performative horizon, are not drawn upon a location but through it – like the mark of paint upon a canvas, or a footprint left in the mud, they serve to mutually redefine this space in which they operate.

Daniel Alexander Hignell-Tully